Trump's inauguration brings high stakes, hopes in rural Minn.

Trump's inauguration brings high stakes, hopes in rural Minn.

Donald Trump didn't win Minnesota. And he never visited Mower County. But his message resonated with voters in LeRoy and Lyle. Now they wonder: What's next?

By Mark Brunswick Star Tribune JANUARY 14, 2017 — 11:09PM

LEROY, MINN. – The morning temperature was 21 degrees and dropping, but winter’s chill and icy roads couldn’t keep the regulars from gathering around the “thinking table” at Sweet’s, a popular Main Street hotel and restaurant for more than a century.

With Fox News on a nearby TV, the coffee crowd, which included a former deputy sheriff and retired and semiretired farmers and truckers, was decidedly optimistic about President-elect Donald Trump.

“We’re the kind of people who believe in country, family and faith — not necessarily in that order,” said Dave Johnson, a semiretired cattle and hog farmer, Trump man and the table’s informal alpha dog. “We’re concerned about the future, and a lot of us voice it stronger than others.”

Across the table was Joe Saterdalen, who hopes Trump surrounds himself with advisers who will change a system beholden to special interests.

“We needed somebody as Republicans who wasn’t previously a politician,” he said.

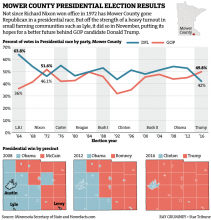

Not since Richard Nixon in 1972 has Mower County gone Republican in a presidential race. Whether it was a sense of feeling left behind, resentment over some of the state’s highest health-care costs, contempt for Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton or a desire to destroy the status quo, what played out here rippled across much of rural America.

Trump didn’t win Minnesota. And he never visited Mower County. But his message resonated with voters in places such as LeRoy and Lyle, both of which backed President Obama in 2008 and 2012. And while Clinton captured the county seat of Austin in November, she did so with 28 percent fewer votes than Obama picked up there four years earlier.

Now, as Trump prepares for the move to the White House, voters here anxiously wonder: What’s next?

“I’m hoping for just something new,” said Sheila Nipp, an Austin resident who usually votes Democrat, but turned to Trump in November.

Nipp’s vote was a personal statement about how unhappy she has become with the way things are working and her fear that Clinton was simply just another career politician. The last time she felt that way was in 1998, when her vote for former professional wrestler Jesse Ventura helped him become Minnesota’s governor.

“Every once in a while,” she said, “you have to shake things up.”

Fueled by anger

Saterdalen said he sensed something untapped was gathering momentum across Mower County this fall by the number of Trump signs he saw as he drove local roads with his Corvette club.

While Clinton received about 3,600 fewer votes in the county than Obama in 2012, Trump picked up about 1,800 more than GOP candidate Mitt Romney four years earlier. What’s more, voter turnout in Austin, which historically leans Democrat, dropped by about 600 voters in November. The result — 19 of the county’s 40 precincts flipped and went Republican.

For many, it was a vote fueled by anger.

On their own, some residents constructed and posted homemade “Hillary for Prison” signs, a reference to scandals that dogged the Democratic candidate. In October, the Mower County sheriff estimated, as many as 60 Trump yard signs were stolen and discarded.

In LeRoy, a town of about 900 residents on the Iowa border, a $15.9 million school referendum also was defeated and the incumbent Republican mayor, who supported it, was ousted.

Johnson said that many here worry about the future of small businesses and local farmers. He said taxes and regulation are less burdensome in Iowa, a stone’s throw from town.

Daniel Evans, the publisher of the Mower County Independent newspaper, sees Trump’s victory as a call for a return to more conservative leadership on issues such as gay marriage and abortion.

“This day and age, everything is veering away from God as far as the government is concerned. People are seeing that, especially in the rural areas,” Evans said over a cup of coffee at Sweet’s. “Hillary had a record and it wasn’t a good record. Trump, by any means, doesn’t have the greatest values either. But he wanted to make America great again. People liked what they heard.”

The stock market has climbed more than 1,500 points since Election Day, and consumer and business confidence has hit levels last seen more than a decade ago. But Trump also has been dogged by questions about conflicts of interest in his business ventures and in his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Verlis Payne, an 87-year-old retired farmer and a Sweet’s regular, hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since Dwight Eisenhower. He predicted the president-elect’s local supporters will come to regret their vote.

“To be honest with you, Trump scares the hell out of me,” Payne said. “This whole Midwest area is dependent on agriculture, and if Trump goes through with what he is proposing, all these tariffs, he will kill agriculture.”

Life in Lyle

The stakes are high across all of America, but maybe nowhere are pressures greater than in small towns, many of which are struggling to survive. The town of Lyle, 23 miles west of LeRoy, is no different.

With a population of about 500, Lyle is the kind of place where a statue of a German shepherd guards a sign along First Street welcoming visitors to the local Memory Gardens. On the south side of town, Lyle Liquor offers $1 hamburgers on Wednesdays and $1 tacos on Thursdays. Most of the letters on its neon “LIQUORS” sign burned out long ago.

The city was named after Robert Lyle, a farmer and territorial and state legislator who eventually moved away to Missouri. At one point, 34 trains a day passed through town. These days, it’s quieter, with most people working for the local school district or commuting to Austin, 12 miles away.

Despite vast stretches of surrounding farmland, dozens of families have pulled shifts and earned paychecks at Austin’s Hormel plant, delivering a reliably blue-collar union vote for Democrats. Politically moderate farmers here also put the “F” in the state’s Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party.

In 2012, President Obama won Lyle and Lyle Township with 72 and 55 percent of the vote, respectively. Four years later, both flipped — 55 percent of the voters in Lyle and 64 percent in the township chose Trump to lead them.

Despite the turn, state Rep. Jeanne Poppe, DFL-Austin, who represents the district that includes Lyle and LeRoy, won a seventh term in the Legislature. She admits she doesn’t know whether November’s election was the start of a revolution or merely a fluke.

“I guess we’ll see,” she said. “In two years again, they’ll have people who will be running for Congress and governor. Maybe they’ll come out again or maybe they’ll stay home. They did their thing and now they’ll let the dust settle for a while.”

Even the local Republican Party, which did not anticipate the groundswell or the anger, isn’t quite sure what comes next.

Mower County GOP Deputy Chairman Denny Schminke, who originally supported Ted Cruz, and also was an unsuccessful candidate for the Legislature, said he isn’t convinced that the election results portend a sea change.

“The pendulum has probably swung too far toward the GOP and it’s going to come back really hard,” he predicted. “Washington will do its thing, which is to obstruct. People will be disappointed and looking for something else.”

Pressing concerns

On a recent Friday night in the Lyle High School gymnasium, the hometown boys’ basketball team faced off against a taller and more muscular Grand Meadow squad. By halftime, Lyle was already behind by 12 points in a game it would lose, 61-40.

But more pressing concerns were not far beneath the surface.

Even if its heyday is past, the pride of Lyle remains with its school. Despite financial pressure to consolidate, local residents have fought hard to stave off any merger. The new elementary school and high school were built in 2006 after four contentious referendum votes. With about 240 students, the school has combined its athletics department with Pacelli High School, an Austin Catholic school, to stay competitive in conference play.

On this night, Sheila Nipp watched the game with her friend, Holly Murphy, who admits she didn’t cast a vote for president. The atmosphere surrounding the campaign was so toxic, Murphy said, that she was concerned she would be pilloried by supporters of either candidate.

Both women, who have sons on the Lyle/Pacelli team, worry about the future. Both admitted being unnerved by a recent incident once unheard of in Lyle: a drive-by shooting.

Police said three shots were fired on Christmas Eve into the Colonial Apartments north of town. No one was injured, but the shooting sparked a town-hall meeting where residents and city officials discussed increasing police presence at the apartments and adding more lighting.

Murphy, an Austin resident who lived in Lyle when her children were younger, said she fears big-city problems have found their way to Mower County.

“I felt safe letting my kid at 9 years old go to the park and not worrying about it. Now I wouldn’t let him do it,” she said.

Like others in town, Lyle resident Joe Bartholomew, who was watching a nephew play, sometimes reflects on simpler times.

He works in Austin in the gas service department at Austin Utilities, maintaining and servicing water heaters, furnaces and fireplaces. While growing up, Bartholomew saw a job at Austin’s Hormel meatpacking plant as the ticket to a comfortable life. Now, he says, he’s not so sure.

He worked at Hormel out of high school but never went back after a long and bitter strike divided the community in 1985 and cost many workers their jobs. Like many here, he believes the subsequent wage cuts changed Austin, sparking an influx of cheap immigrant labor and transforming the demographics of a city where 44 languages are now spoken, according to the local school district.

Austin’s Hispanic population has more than doubled since 2000. That’s a far cry from what Bartholomew sees when he drives home from work to Lyle, which is almost entirely — 93 percent — white.

Bartholomew said he now wishes he had taken Spanish in school. When he goes to a customer’s house in Austin, he must often get the children to translate for their parents.

“The influx of the people [Hormel] hired, at first there was bad feelings,” he said. “Over time that’s eased. You don’t think about it so much anymore.”

Lyle native Mitch Helle is preparing a history of the town for a book to be published in 2020, marking its 150th anniversary. As part of his work, Helle asked residents what they hoped Lyle would become in 50 to 100 years.

The most optimistic response, he said, is that it will be more of a bedroom community for nearby Austin or even Rochester, about 50 miles away.

“Maybe some people will want a small-town life and a smaller school to send their kids to so that they can participate in everything,” he said. “Something like they thought it used to be.”

Data Editor MaryJo Webster contributed to this report.